Retrieved: 12/07/2013

This isn't a build, just some notes I've been making about how I might go about building a revolver from scratch. Perhaps it will give someone some ideas.

Modern revolvers are quite complex; precision castings finished with pin mills and CNC equipment. To whittle something like Model 29 or Security Six out of a block of steel would be more work than it is worth.

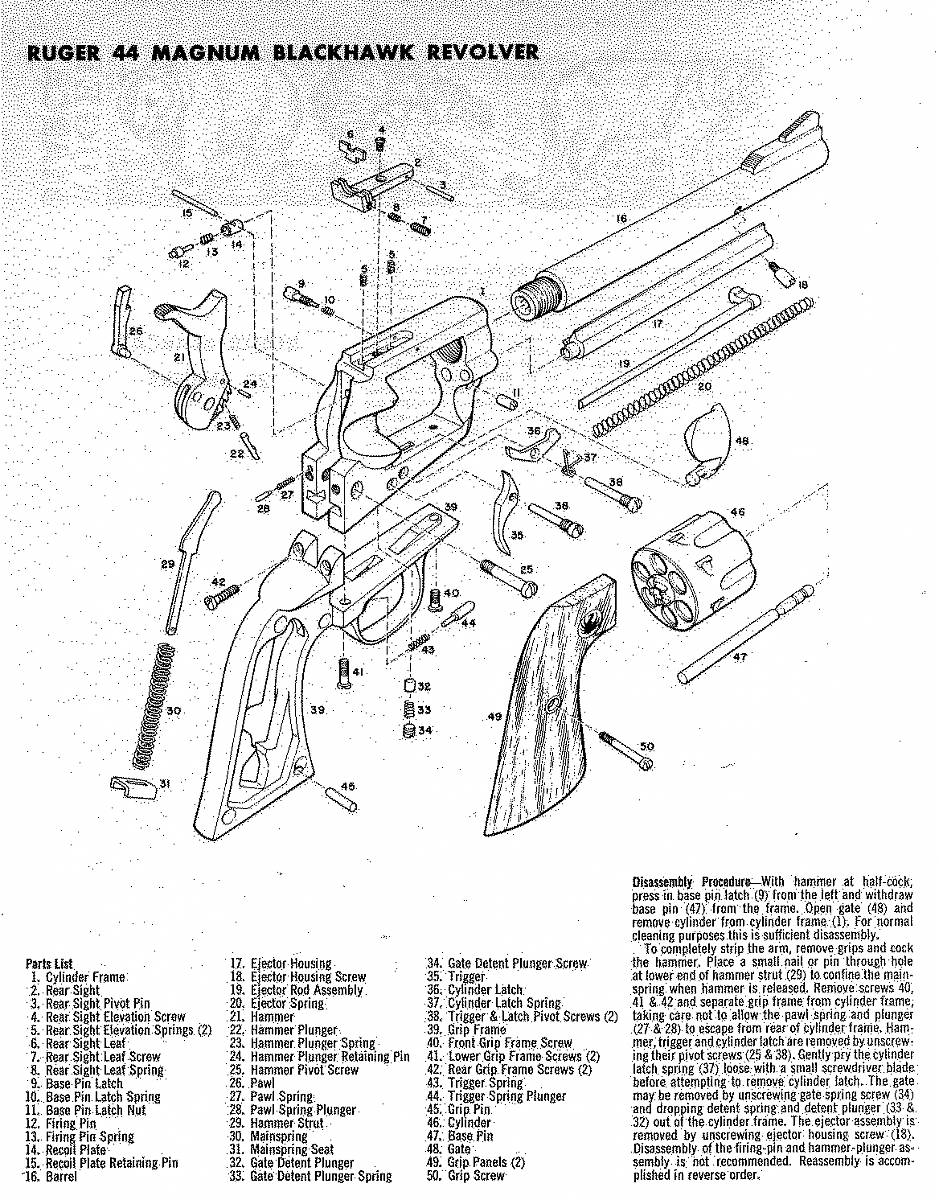

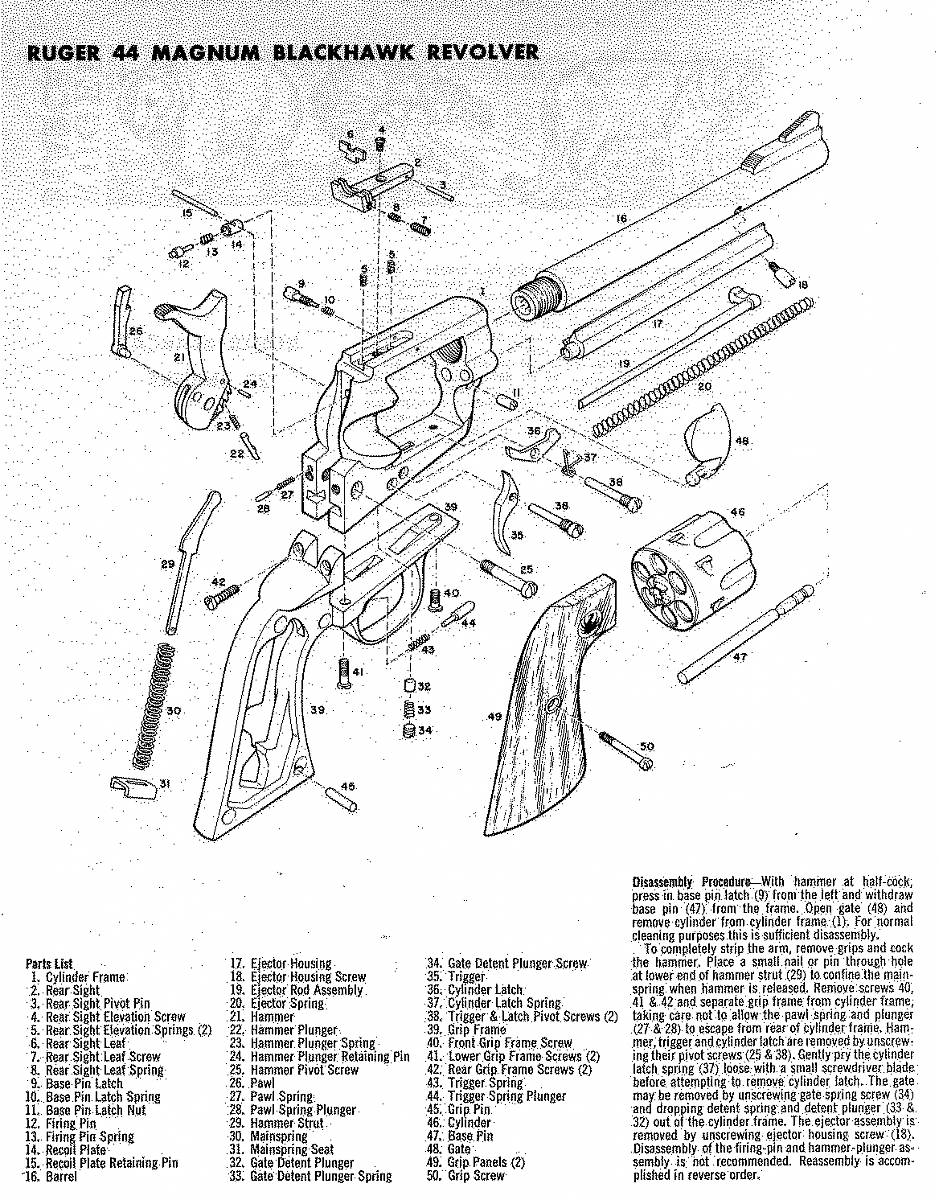

However, if you look back at the old Colt Single Action Army, you see a frame that's made out of several small parts. The Ruger Old Army (picture below) is very similar, except it combines the two grip pieces into one.

The part I stalled at for a long time was the frame behind the cylinder, the "cheeks". Easy enough when you start with a casting, but a hassle when you start with a billet. It could be done with CNC, but I wanted a design that could be done without that. I finally realized the cheeks have no structural purpose; they're just there to keep the cartridges from falling out.

(Asimov spoke of the "Aha! moment", where someone comprehends a complex concept in a flash of inspiration. I'm more prone to "duh! moments", where I trip over the bleeding obvious...)

In this case, we could cut a hemisphere on the lathe, slice some sections from it, and attach them to the sides of a frame made out of 3/4-inch or so flat stock. (duh...)

The next problem is how to make the rectangular hole for the cylinder. Factories cast them nearly to size, then finish them with long broaches. You could mill the hole and file the corners. I know there are guys out there who are wizards with a file, but I wanted to just machine a hole.

Inspiration came when I was looking at some pictures of some really old revolvers. Most of them had a fat radius on the back of the cylinder. They were cap-and-ball pistols, so it didn't hurt anything... but you could put a nice radius on both ends of the cylinder without hurting things much; cutting the opening with a 1/4" end mill (1/8) radius might work okay. Or drop down to 3/16 if you insisted. The rounded corners would also make the frame stronger.

Flat stock, make a hole, attach the cheeks, mill a slot for the trigger, drill and tap for the barrel, some minor machining here and there, and you'd have the frame.

The hand and cylinder timing threw me for a long time. I used to have some nice D/A revolvers, and they were full of intricately-shaped fiddly bits to make all the stuff happen. Lots of complex machining there. But the old Colt and Ruger S/As are quite simple inside. Of course there's no D/A mechanism, no modern transfer bar to block the hammer, etc. Simple doesn't come for free. The only parts that would require awkward cuts are the slots for the cylinder latch and trigger. Keyseat cutters and I just don't get along, but there are only two of the slots to do.

The cylinder comes next. The usual method is to set up on a mill with a rotary table to do the cartridge holes (and flutes, if desired) then set up again on an indexer to do the latch cuts.

I'm still at a loss on how to cut the ratchet on the back of the cylinder. Everything I've come up with requires two or three setups and fiddly cuts. To the plus side, the ratchet doesn't have to be all that precise; it just has to get the cylinder indexed close enough for the radius on the end of the latch (part 36) to push it the rest of the way into position.

If it came down to the nitty gritty, I could cheat, buy one of those thimble- sized jewelry crucibles, use my torch to melt a piece of 4140 scrap in it, and pour it into a lost-wax mold made from a production cylinder. Then I could just silver-solder my "ratchet button" into the cylinder.

The bottom frame isn't nearly as complex as it looks. Both the Colt and Ruger designs are wasteful of metal if you whittle them from plate, but you could blacksmith the straps on the Colt into rough shape, starting with some flat stock. You could weld the trigger guard on, etc. A bandsaw and spindle sander would take care of most of the shaping.

Almost every part has a crown or radius. Some of it is to reduce weight, the rest is for styling. Duplicating every curve exactly would be a hassle, but not really necessary to build a shooter. "Detail shaping is left as an exercise for the student."

Looking at some pictures today, I realized why so many big caliber revolvers are 5-shot instead of 6. The usual given reason is "more metal between the cartridges." True... but for a six shooter, the indexer cuts are right in the thin spot over the cartridge. For a five shooter, they're in the thick web between the cartridges. An odd-number cylinder would therefore always be a bit stronger than an even-number cylinder of the same diameter.

TRX

01-08-2011

I found a build where someone made a new cylinder for his revolver. To ensure that the index was correct, he made a drill bushing to replace the barrel, then drilled the cylinder in place, indexing it to each position, before removing it to run the chamber reamer in from the other end.

It also occurred to me that there's no reason you can't run a rimless cartridge like the 9mm Parabellum or .45 ACP if you have a revolver with an ejection port and rod instead of a swing-out cylinder. You only need a rim when you're trying to eject cases from a swing-out cylinder, so the extractor has something to get hold of. Since there's no extractor on a typical SA design, it doesn't matter if there's a rim or even an extractor groove, as long as the cartridge headspaces on the case mouth, anyway.

TRX

01-10-2011

Someone already builds one in .30-30. The "angel wings" from the cylinder gap must be impressive in the evening...

TRX

01-14-2011

I've been reading up on the use of bottleneck cartridges in revolvers. One group says the bottleneck cartridges will set back and jam the cylinder where it won't want to turn. Another group says it's a non-issue. Both point to production bottleneck revolvers as proof.

If you built a revolver with a bottleneck cartridge and had setback problems, one way to fix it might be to relieve the back of the frame a few thousandths, except for the area right around the firing pin. As long as that one case didn't jam the cylinder, the cylinder would turn freely to the next after the fired case cleared the hump.

Almost makes me want to build a revolver in 7.62x25 just to find out...

TRX

11-06-2011

Timing the cylinder on a revolver is a tricky machining task. There's a small, precisely-machined slot in the bottom of the frame for the latch. The latch engages in the slots in the cylinder, which are precisely indexed to the chambers. Even then, indexing isn't as precise as it could be, so the end of the barrel is cut with a conical counterbore to funnel the bullet into line with the rifling.

Then there's the Nagant revolver. Its main feature is that the cylinder slides forward slightly and the end of the cartridge (the bullets are seated flush) slides into the back of the barrel. Lore says this is a "gas seal", and that it's worth about 50 feet per second on muzzle velocity.

This sounds logical, until you realize the Nagant was designed from scratch, along with its ammunition. The .30 Nagant is weak-kneed by 21st-century standards, but if they'd wanted another 50 fps, they'd've probably just loaded the cartridge hotter.

I was looking at some exploded views and suddenly realized that the "gas seal" might have been intended for an entirely different function - to line the cylinder up with the barrel. No coned barrel, no index errors, dead-nuts alignment every time.

Note the USSR used the weird old Nagant revolvers (and variants thereof) for a long, long time in international target competition, and did quite well, too.

TRX

12-08-2011

I recently acquired a Nagant revolver. Inspecting the mechanism... there's no appreciable "gas seal" involved. There's no cylinder latch, either. As I suspected, the "gas seal" is the way the cylinder aligns with the barrel.

Since there's no hand, you can turn the cylinder by hand as long as the trigger isn't pulled.

Despite all the monkey-motion with the cylinder moving forward, the trigger pull is no longer (or worse) than many modern double-action autoloaders.

It's also double action - you can pull the trigger and fire, or cock it first. If you cock it first, the let-off is quite nice. In double action, the first stage (it's very definitely a two-stage trigger) is noticeably crunchy, though.

I *like* this gun. When I get time I'll take it apart and examine its naughty bits.